A brand―a trusted solution that meets the expected psychological and utility needs of the purchaser―is an important competitive differentiator. Having a brand means one’s product or service is chosen more frequently over similar solutions, and one can command a price premium, which results in greater profitability.

A brand, however, is not owned by the company that manages it—it’s the intellectual property, including service marks and trademarks behind the brand that are. Instead, the consumer who experiences the product or service elevates it to brand status, thus exercising “ownership.” [See previous post, “You Don’t Have a Brand.”]

What makes a brand, then, is the implied agreement by the consumer that the product or service delivers the desired experience repeatedly, so that switching to another solution is not a consideration (unless under duress). A brand is a primary choice, and often a secondary choice may not even exist.

To be considered a brand, a wide adoption must be in place in the target market; a brand is a social experience validated by other consumers. The market for the product or service does not need to be large—luxury markets are narrow segments of the population—but the penetration should be significant and profitable.

If the customer loses faith in the brand’s ability to deliver the expected or promised experience, and he/she instead begins to choose another solution repeatedly, then the original solution has lost brand status. If this happens on a large scale with an incumbent customer base, then the product as a whole loses brand status, suffers market share losses, and cannot maintain its pricing, for it has not maintained its promises and differentiation.

This risk is what makes a brand not just an intangible but an ephemeral asset, and therefore necessitates constant vigilance in brand protection measures.

The Brand Steward: A Definition

If the owner of the brand is the consumer, what is the company that owns the intellectual property? It is the “brand steward.” Although the company originated the product, its success was created by the purchaser. Certainly, a company must take great care to foster an environment that will give the product the greatest chance of success at brand status, but there is no guarantee of success, only preparedness.

The brand steward is thus entrusted with caring for an asset that is highly valued by a sizable consumer community, which wishes for the product to continue to deliver the same, or better, benefits. However, this steward is not a person—even though there are “brand managers”—it is the entire organization behind the product or service.

This organization is made up of various departments—executive leadership, R&D, manufacturing, sales, marketing, customer care—that must work together to continuously meet the promises offered by the product, and the expectations these promises have created within the customer.

Because brands are ephemeral, the entire organization is tasked with keeping the product alive and relevant within the expectations set by customers, so that the product will continue to be a primary choice for the longest time possible. Sales, marketing, and customer care interface directly with the customer on a regular basis, making these departments particularly responsible for carrying out careful brand stewardship activities. But R&D and executive leadership are equally important, as their work affects the direction of a product or service to which customers have attached brand status.

The customer may not always be right, but the customer can always damage the brand. As a consequence, the company stewarding the brand should make every reasonable effort to prevent a lasting poor impression in case of a brand experience failure by a customer. Further, the company should leverage failure into an opportunity that causes the affected customer to praise the company and its product to others. This is how brands are maintained.

Ultimately, not one person but the entire culture of a company stewards a brand.

Stewardship Roadmap

To innovate and keep a brand alive, a company must regularly engage in market research to learn how its product performs against customer expectations, and also to learn what additional value the customer would like to receive. These findings must then be tested against the brand’s ideals (its mission/mantra), compared against competitors’ existing capabilities, and validated for market acceptance within the incumbent customer base.

Sometimes the customer does not want change (“New Coke”), but customers often value continuous improvement, as long as these improvements are in keeping with the brand’s ideals and differentiating factors (iPhone 5)—the reason for why the product or service was chosen in the first place.

Sameness does not a brand make. Think evolutionary, not revolutionary.

Thus, in addition to collecting meaningful customer insights, a company must (1) have a framework against which to evaluate potential product changes, (2) the know-how to make those changes in accordance with customers’ wishes, and (3) the ability to communicate and support these changes. This entire process is called brand stewardship.

(1) The Positioning Journey

When the marketing department (often the customer/consumer insights division) has observed or learned of a new benefit the customer would like to receive from an existing product or service, the typical next step would be to test the possibility of adding this value (a feature) and costing out this process, including its effect on final price.

However, the first step should be an analysis of how this additional utility affects the perception of the brand. Just because someone has requested something, or a competitor has added a feature to its product, does not necessarily provide good enough reason to incorporate the same change into one’s own product. Parameters must exist against which the viability of an idea can be tested against brand perception

To do this, a company must understand itself, its product, and the competitive landscape. In case these analyses have not been performed in the past, basic strategy tools exist to help produce the answers to each of these questions. With these answers, the company can very clearly define the positioning of its product, enabling it to compete effectively, and better evaluate future product innovation and feature requests.

Positioning

In combination, SWOT, VRIO, and Five Forces analyses help a brand steward figure out (1) what the company itself is capable of, (2) how the product or service is presently positioned, and (3) what competitive forces the company is facing. These basic insights are critical to helping the company create the correct positioning and customer expectations that can help elevate a product to brand status, or maintain an already earned brand status.

Positioning is more than just deciding to produce a luxury or a mass-market product or service. The company must envision its customers and figure out why they would be attracted to the product. This is the most difficult step, because it involves making long-term strategic decisions that affect customer adoption and competitive positioning.

While the consumer will ultimately decide the positioning, value, and utility of the product that can lead to brand status, the company needs to get its initial positioning right―it must define the core essence of its offering to which a self-selecting audience will be attracted.

Positioning is not necessarily permanent, but it must be impactful the first time to permit future adjustments. Apple Computer did not start out as the world’s largest digital music retailer, but its original positioning as a computer design and manufacturing company which understood the wider implications of “personal” computing, enabled it to successfully transition the Apple brand into new markets, with even greater brand equity as a result.

Analyzing the Company: SWOT

A SWOT analysis is probably the most commonly used strategy tool, and examines the overall ability of a business. It asks the following questions of the company:

- Strengths: What do we do well?

- Weaknesses: What do we do poorly?

- Opportunities: What can we exploit?

- Threat: What external threats do we face?

The analysis process should include members from the aforementioned departments in order to get a wide variety and inputs to help create a complete picture. If necessary, an external facilitator should manage this process to keep potentially strong political forces at bay and to assist in collecting all valuable input.

First, the company needs to look inward and review its own strengths and weaknesses. What is the company good at, what are its core competencies? The answer can include any number of things, such as design, customer service, and patents. Where does the company underperform and how might those areas jeopardize the idea’s success? Again, any number of things can be identified, such as project management, distribution, and key employee retention.

Next, examining opportunities and threats takes into account external factors over which the company has little or no control. What opportunities can the company’s strengths create for the idea? Is its marketing better than that of its competitors? Does it have a more resilient supply chain with less country risk or pricing volatility? And what threats do its weaknesses expose it to? Does it have poor distribution that would keep it from rapid market penetration? Or does it lack the ability to scale customer service? Are some competitors simply better at some things, which could put the company at a market disadvantage?

The more precise and quantifiable the SWOT analysis, the more valuable its information and results will be for long-term strategy planning. Knowing one’s own strengths and weaknesses, as well as the external opportunities and threats that these strengths and weaknesses can exploit or create, is critical to successful product planning and potential brand success.

Analyzing the Product: VRIO

A VRIO analysis is not performed on the company (that’s what SWOT does) but on its inputs or outputs. VRIO is used to analyze the proposed service or product, or the requested change.

- Is the product Valuable? Does it help meet a threat or exploit an opportunity?

- Is the product Rare? Is it not already a widely available solution?

- Is the product (in)Imitable? Is it difficult to copy or easy to defend?

- Is the company Organized? Can it readily exploit the product and repeatedly deliver on all of its promises?

The obvious answer is that the more valuable, rare, and difficult to copy the product or service idea is, the more advantaged the competitive positioning will be. This is critical in evaluating any proposed change. How would such a change affect the value, rarity, or imitability of the product or service? Does it lead to homogeneity, or does it create further differentiation, driving VRI?

Any successful/profitable product will ultimately cause others to enter that market. The most difficult thing to copy, however, is not a product or a service, but the execution of that, which itself is driven by the corporate culture behind it. How well a company is able to defend its output over time is therefore a matter of how operationally well it executes—how well organized the company is, and how well it communicates internally.

The better organized a company is, the more difficult it is to imitate its success, and the better protected the brand is.

A baseline VRIO analysis needs to be crated first, so that any new product or service idea can be evaluated in context. If the new/revised idea maintains or increases competitive differentiation and can be brought to market cost effectively, a defensible competitive advantage with favorable economic implications will have been maintained or increased. The opposite needs to be avoided!

Analyzing the Competitive Landscape: Five Forces

A Five Forces analysis examines an industry’s overall structure and the competitive external pressures a company will face. It provides further context against which to evaluate the outcomes of the SWOT and VRIO analyses.

Five Forces includes the following points of analysis:

1. Research any direct competitors. The more unique an idea—tested or re-adjusted via VRIO—the greater the likelihood of the idea’s short-term survival, as few or no direct competitors will presently exist.

2. Quantify the risk of new competitors entering the space. Can current pricing be maintained in the face of cheaper competition? Is the product attractive or defensible enough (think patents or market share) to ward off new entrants wishing to encroach on its market share? What inputs can the firm dominate to keep competitors at bay?

3. Identify the possible threat of substitutes. Substitutes are dissimilar solutions with similar benefits (e.g., portable digital cameras being displaced by smartphones). What can solve the same problem differently? Will the product remain relevant in the face of competition by substitutes?

4. Determine the bargaining power of the company’s customers. How much power can customers wield to affect pricing? If a company is dependent on a few customers for most of its business―e.g., 80% of revenues generated by 20% of customers―its top customers can dictate what they will pay; unless the company has a monopoly, which is a situation customers will try to avoid by seeking out substitutes.

5. Determine the bargaining power of the company’s suppliers. Suppliers provide raw materials, ingredients, or components, but even the labor market itself can be a supplier if the product is intellectual property such as software. If a company depends on only a few suppliers for the majority of its inputs, these suppliers can charge whatever they want, because their pricing is inelastic.

As a first rule of thumb, the brand steward wants to occupy a market space with the lowest potential for both new competitors and substitutes. The more unique an offering or positioning, the fewer direct and indirect competitors will need to be dealt with.

As a second rule of thumb, the company needs to avoid buyer and supplier monopolies because of the risk such exclusive dependence poses to a company’s ability to generate significant profits that can be reinvested into brand stewardship. Management should seek many suppliers and customers so that none can create a bottleneck in production or dictate pricing that would jeopardize the product’s viability or a brand’s status.

In summary, brand stewards need to know:

- What the company is capable of and what its limitations are (SWOT).

- How the product/service is different, or needs to be differentiated (VRIO).

- What the competitive landscape is and who holds power (Five Forces).

Once the brand steward has figured out the product’s uniqueness and competitive white space, product innovation or changes can then be better evaluated.

During this phase of brand stewardship a company is tasked with maintaining and further enhancing the positioning and identity of the product that the consumer has deemed critical—not that the company itself has decided is most important.

(2) The Customer Experience Phase

Marketing is the process of getting one’s product or service into the marketplace, noticed, and bought. Therefore this includes traditional marketing activities (such as promotion and advertising, which communicate positioning and create expectations), sales people (who further communicate positioning and create expectations), and customer care activities (which manage incongruities of positioning and expectation).

A sale is not truly complete or successful unless the customer’s expectations have been met. The customer care department’s role, therefore, is to help the customer avoid buyer’s remorse, making customer service and care a marketing activity in and of itself.

Marketing communication activities (including promotion and advertising), sales promises, and customer care activities must all fully understand the product’s positioning in order to carry out brand their brand stewardship responsibilities. Does the execution of sales and marketing tactics communicate the product’s intended brand ideals? Have the promises implied in the company’s positioning been carried all the way to the customer?

When any of these MarCom activities, including customer care, touches the customer, it is critical that they act and communicate in one voice with one message. Otherwise, if incongruities in messaging and positioning do occur, it is possible that customers will become confused and differentiation will be lost. As a result, brand perception will slip in status.

To manage and optimize cooperation and interoperation among sales, marketing, and customer care activities, one first needs to determine what gaps may exist in these processes.

The Services Gap Model

Brands can only come into being when the correct expectations are set and delivered. Executive management makes product feature and positioning decisions, which must then be communicated by the marketing department, implemented by the sales or services departments, and supported by post-purchase customer care activities. Here a variety of disconnects can happen. Is the promised experience envisioned by management, promised by marketing, delivered by sales, and supported by customer care congruent with the customer’s perceived experience?

The Services Gap Model provides a framework for understanding and improving service delivery, and thereby customer experience, which directly affects brand perception. Even when the item sold is a product, not a service, the framework remains applicable because intangibles that are perceived as services are always involved in delivering a good.

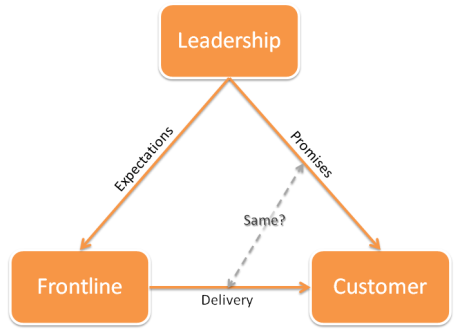

Figure 1: The Services Gap Model Triangle

Executive leadership makes “executive decisions” about a product or service; marketing encapsulates these as value propositions; sales communicates these value propositions to customers; and customer care deals with customers when the promises thought up by executive leadership, encapsulated by marketing, and communicated by sales are not perceived by the customer.

Clearly, communication breakdowns can happen at every level and juncture.

(1) How has executive leadership learned what the customer wants? Through direct interaction with the customer, or though surveys or other traditional quantitative research methods? If those who set the tone—who are responsible for defining positioning—have little to no engagement with real customers, then critical decisions related to product positioning (features and benefits) are made in an information vacuum, and often may not be customer-centric. If insights were gained through direct customer interaction, it is rather more likely that leadership will have a well-informed understanding of what the market really wants, as well as what the market does not need. This does not negate the need for aggregate market research, however.

Therefore, the highest echelons of the company must be involved with the customer, even if only from time to time, so that the true customer desires are learned, their solutions implemented, and the correct promises communicated back. This avoids or minimizes the occurrence of the customer having a different experience than was promised, which is important for maintaining brand identity and loyalty.

(2) Executive leadership and marketing (who encapsulate leadership’s value propositions) must also have a rapport with frontline staff, and must regularly inform customer-facing departments of what was learned during high-level interactions with customers, and how that might have affected messaging and positioning.

Further, by empowering customer-facing departments to remediate customer experience issues immediately, without frequent escalation, customers whose expectations were not met can still be converted into happy customers (or into happy non-customers who at least will not damage the brand’s reputation). This avoids or minimizes the occurrence of the customer perceiving a different experience than was delivered, which is equally important for maintaining brand identity and loyalty.

But communication is not a one-way street. If properly trained, frontline staff can listen to customer ideas and complaints, and report upward the best ideas and greatest failures as reported by customers. Therefore, frontline people are exceptionally well positioned to learn, summarize, and communicate important ideas and experiences from highly valued and profitable customers, as well as new ideas that may lead to additional product differentiation not previously considered. Those ideas will then need to be evaluated against the strategy frameworks discussed above, but the fact that these suggestions have come from existing satisfied customers gives them additional credence for consideration.

The two, communication and empowerment, may seem like separate issues, but both are focused on customer satisfaction, either by encapsulating and messaging the correct promises, or by fixing perception issues when promises were not met correctly the first time. This also helps avoid the very unfortunate occurrence of a customer’s experience being different from his or her expectation of that experience, and tests and validates the organizational capabilities of the company.

(3) Obviously, companies know that over-promising and under-delivering is the most assured recipe for failure. Few know that the opposite—under-promising and over-delivering—can be damaging, too.

Instead of trying to give customers the best experience ever, which should be a goal but not necessarily a stated promise, leadership needs set expectations in the positioning, marketing, and sales phases that can be met repeatedly.

When a firm temporarily over-delivers on product reliability, features, customer service, and so on, it has likely raised the expectations bar permanently. Disappointment will later ensue should the original—but now superseded—performance levels take hold again. For example, If 24/7 world-class service has been promised, then that expectation must be met. But if 18/7 world-class service has been promised and the firm delivers at a higher level, then customers will be disappointed if the company later falls back to 18/7 world-class service.

Therefore, brand stewards must make promises very carefully, and ensure that these promises are met continuously without fail.

So the Services Gap Model recipe is simple:

- Customer experiences that are incongruent with customer expectations must be avoided.

- All departments, including executive leadership, must listen to customers.

- Internal communication about customer expectations and experiences must flow both ways, up and down.

- To turn negative customer experiences into positive ones, employees must be empowered to resolve issues without frequent escalation.

The Customer’s Journey

So far we have discussed strategy schemes for competitive and strategic positioning wrapped in a customer-centric R&D and services approach. Next let’s discuss actual customer needs.

The customer’s thought process on purchases always boils down to the following:

- “I have a need or a problem.”

- “Is there a solution out there I already know and trust?”

- “If not, let me do some research.”

- “This product/service is purported to be great/terrible/okay.”

Obviously, the potential customer will not reach step 3 if a default solution is readily available. However, should the potential customer reach step 3, it is critical that the brand steward has positioned and made available its solution in such a way that it seems the obvious next choice. This is no longer achieved simply by having dominant shelf space or an appealing advert in the Yellow Pages.

Since the advent of the commercialized Internet, traditional advertising has become less and less effective. The Web has given nearly every person the ability to perform research on products and customer satisfaction. And social networks have enabled instantaneous and asynchronous communication with trusted advisors (friends and family, colleagues, hired professionals) to receive product recommendations anywhere in the world.

Additionally, potential customers do not rely exclusively on personal relationships for product recommendations; they also rely on other trusted networks to aid in discovery and decision-making. For example, new mothers who are otherwise complete strangers may congregate at CafeMom.com to share experiences and recommendations. In-person Meetups (www.meetup.com) take place on an infinite variety of topics across the globe, allowing complete strangers to share their interests and passions. Customer reviews on Amazon.com and Zappos.com serve the same purpose of sharing product and service experiences. In any of these situations, the opinions of strangers are treated as expert recommendations that can at the very least lead to a one-time trial of a suggested solution.

This new landscape is why customer satisfaction—which can lead to customers becoming net promoters (rabid fans who promote and defend a company and its offerings)—is very important, and why incongruities between the expected and perceived customer experience need to be minimized or eliminated. This is also the reason why traditional advertising is becoming less effective, and authentic endorsements from trusted resources is the most effective form of marketing.

While advertising is still relevant, a brand steward’s responsibility is to be an active member of the communities that have embraced and are talking about its products. Red Bull Energy Drink is a prime B2C example of how a brand steward has become part of the community that champions its product. In B2B, marketing materials such as believable client video testimonials must be available collateral in places where potential customers perform their research before reaching to the company for further information—the least and last of which is the brand steward’s own website.

As the saying goes, you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink. Likewise, by being visible and authentic in the arenas and communities where customers participate and start their research, brand stewards can effectively enlarge the pond so that the proverbial horse no longer has to be led to it.

The other critical component is the long-term, post-purchase experience. Customers will forgive product mishaps if they receive the proper care and support. To win at this stage, management must have empowered frontline employees to resolve issues without the need for frequent escalation. Spending a little on customer satisfaction returns a lot in customer lifetime value. Or, to co-opt yet another cliché, a customer saved is a customer earned (perhaps even a net promoter).

Have You Been Listening?

Brand is the perception of how an offering is positioned and whether a buyer’s experience was congruent with his or her expectations. It is rare that a company is permitted by the customer to attempt a brand do-over, because customers don’t wish to relearn how they think about a product or service.

In the journey from evaluator to customer, people typically wish to make choices that represent little risk, especially as the monetary cost of these choices increase. It is therefore the brand steward’s responsibility to understand the customer and then incorporate that understanding into product design, delivery, and support. The innovation/improvement cycle can only succeed if the brand steward keeps this ultimate outcome in mind: that experience matches expectation.

If the brand steward (including executive leadership) listens only to customer complaints in the hopes of fixing them, then it is too late to listen to the customer. Listening is a broad and active process. Brand stewards need to listen to everyone who interacts with the customer, not just the customer itself.

Further, brand stewards should not listen only to downstream and in-house suggestions and outcomes, brand stewards also need to listen upstream: suppliers also need to become part of the conversation about customer satisfaction and continuous improvement. And the upstream also needs to be connected to the downstream: suppliers need to be enabled to listen to their customers’ customers. With this process, brand stewards can build a complete chain of information trust, and may discover additional efficiencies and opportunities for product or service enhancement that will deliver value to the customer.

Cheat Sheet

To steward a brand successfully, follow these basic steps:

- Create a multi-functional brand stewardship committee to collect and evaluate new ideas.

- Test and refine ideas against strategy frameworks to assure continued positioning and differentiation.

- Keep your promises: only make promises and implement as ideas when these can be delivered on repeatedly.

- Measure to see if the promised experience matches the perceived customer experience.

- Pinpoint areas in your processes and organization that have led to customer experience mismatches and develop processes to fix them.

- Listen and learn: participate in and add value to communities where large numbers of brand consumers and advocates aggregate.